Chart Vizzard

Vizzlo's AI-based chart generatorNot another “productivity hack” post

On the endless search for becoming better

There is little doubt that having goals and being organized are the first steps to getting things done and moving forward. However, there is something about self-improvement tips and frameworks that makes many of us a bit skeptical about this growing trend. While becoming a better person should be a life aim, many of us believe that there is too much senseless “optimization” being promoted through the many apps, articles, and books circulating out there.

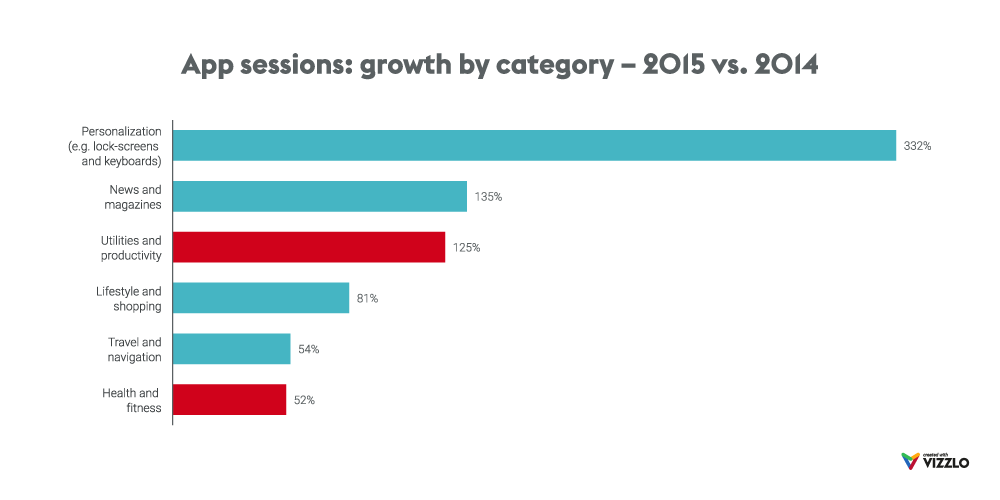

Finding something to “optimize” in our lives is pretty easy, which might explain the huge market behind this trend. But if we would dedicate ourselves to follow every “step,” “method,” or “hack” to increase our productivity, probably nobody would ever get things done. Yet, simply ignoring smart advice from trustworthy experts, especially if we have the feeling that we could do something better, is just pointless.

Does being more productive make us better?

Not necessarily… Or should we first ask what is “better?”

On the one hand, the mere obsession with quantifying, improving and comparing every aspect of life cannot be an end in itself. On the other hand, any list of “should-have” qualities and goals offers only very arbitrary and normative parameters to define and measure what is “better.”

At this point, we should ask why having a productive lifestyle (that also includes being healthier) affects our sense of worth as persons.

The economics of becoming better

The existing market and discourses around the “ever-more-productive” being (also outside the workplace) have a very capitalistic logic behind them, and their expanded reproduction into other non-economic spheres affects the organization of life as a whole. The endless need to increase productivity has become an essential part of our Zeitgeist and somehow “natural.”

Therefore, it makes sense to take a critical approach when applying this economic concept to our lives. Increasing productivity is more than a means to “getting things done.” Measuring productivity is measuring the efficiency of production; increasing productivity is increasing production outputs and/or decreasing inputs. In other words, doing more with less (time, costs, resources, people). That’s why many of us perceive this growing productivity “trend” mostly as an enormous pressure.

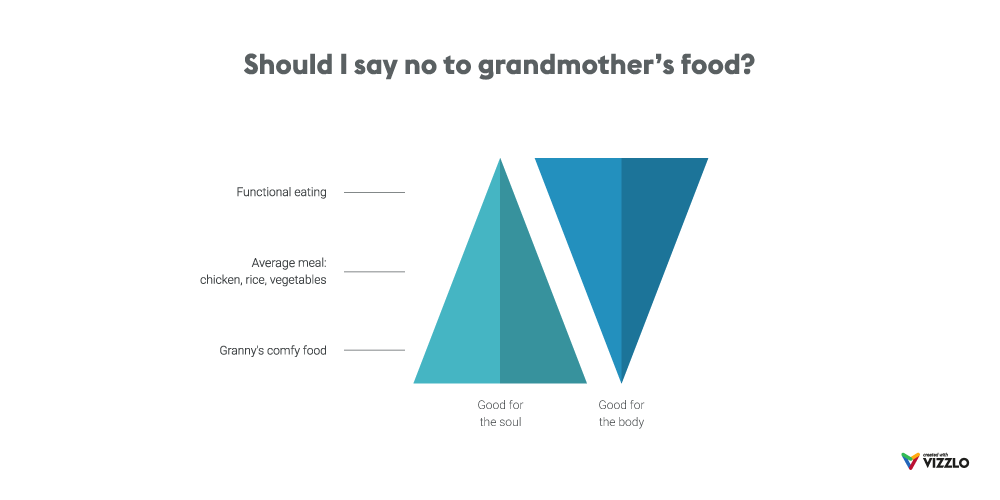

In practical terms, productivity hacks and methods can indeed help us fight our way through everyday challenges, but we should never forget to ask some tough questions before applying them to our lives: Who will benefit from it? Why/how? Is the effort worth it? Other easier questions are also necessary: Do I benefit more from reading a chapter of a great book a day, or should I go for Blinkist? Isn’t eating gramma’s cake good for the soul (despite it not being functional)?

There are only very personal answers to these questions. After all, the quest for increased productivity has become part of the search for a work/life balance and even happiness.

Is there a more effective method to become more productive?

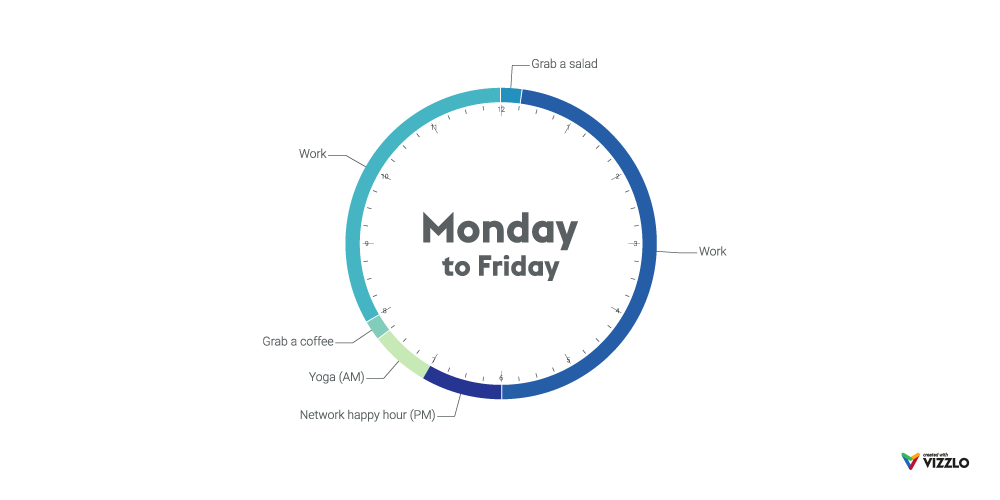

Probably nothing is more productive than simplicity. In many cases, people just get overwhelmed by keeping track of work, diet, sleep, exercise on apps. And after investing many hours in feeding the phone with data, they just drop their efforts, leaving the problem without a solution.

Tackling a problem or changing a habit goes beyond employing popular techniques, apps, and complicated workarounds. A good example of this is the freelancer who decides s/he needs to be more productive during work hours to have more time for friends and family. Quite often, the adopted framework doesn’t improve either the quantity or the quality of the free time. Maybe it has positive side-effects, but the very simple step of sparing time for friends and family remains untaken.

Obviously, what works for others might not work for you

In an interview at the Harvard Business Review, Frank Saucier (executive and Agile coach at FreeStanding Agility) explained how he uses Kanban and Scrum at home. While you might think that making family life more “productive” and managing it as a “project” sounds awkward, he explains how his family communicates and exchanges ideas, feelings, and tasks using these methods. This includes a routine that gives room for everybody (also the children) to talk about everyday life, emotions, and wishes; offer critiques; and work together on a plan. Nobody can say: this is unhealthy for family life.

What Saucier’s example shows is that being “effective,” or more “productive,” is not only about reaching a destination faster but that the journey (independent from how you shape it) in our super-productive world still matters. It also shows that these self-improvement frameworks don’t always mean a time-saving shortcut (they’re sometimes arduous and mean more work), but they are helpful in setting priorities, finding the time for these priorities and using it well, and they can lead us to our goals.

The search for new approaches to become better persons/improve ourselves is probably endless. There will always be new challenges and, fortunately, we will never be able to find a consensus on “perfection” or, at least, on what is good enough. But we definitely should talk more about our objectives and why we are pursuing these. If we’re putting so much effort into it, we should be able to produce more meaningful outputs.